IN THE LATE SUMMER of 2005, a small group of coffee roasters visited a fourth-generation coffee roasting company located in St. Louis, Mo.--Chauvin Coffee Company. As president, the late Dave Charleville, gave a tour of his facility and answered questions regarding his operation. As all of the roasters on the visit were running operations much  smaller than Charleville's, many had questions about Chauvin's packaging equipment. When asked how to choose the proper packaging equipment and when to purchase it, Charleville gave an answer that was both insightful and incredibly helpful. "Always buy capital equipment for the long term," he said. "Make absolutely sure that it makes your operation more labor efficient, and make sure that it is flexible and scalable."

smaller than Charleville's, many had questions about Chauvin's packaging equipment. When asked how to choose the proper packaging equipment and when to purchase it, Charleville gave an answer that was both insightful and incredibly helpful. "Always buy capital equipment for the long term," he said. "Make absolutely sure that it makes your operation more labor efficient, and make sure that it is flexible and scalable."

If one were to survey professional roasters, and the owners of wholesale roasting facilities to find out what area of the production process consistently gives them the most headaches, there can be little doubt that the overwhelming answer would be packaging. Furthermore, it is in the packaging of coffee, from opening and forming the bags and filling them accurately to labeling and applying resealables--be they tin ties, resealable tape or zip locks--where coffee roasters lose the most control over their labor costs. If roasters look closely, many will find their shrinking or non-existent profits are a result of inaccurately accounting for packaging labor.

Choose the wrong material or use poorly considered art and sales will suffer; choose the wrong piece or combination of pieces of packaging equipment and labor costs will rise. And while it is relatively easy to figure the costs of material in a package (bag + label(s) + tin tie), it is much more difficult to figure labor costs per package.

So if packaging coffee is so problematic, why undertake it at all?

Why?

There are four reasons for consumer food packaging, all of which are relevant to coffee: 1) To convey the product from processor to consumer in a convenient manner 2) To preserve product freshness 3) To protect the product from shipping damage 4) To sell the product

To put this in one statement, it would go something like this: The interdependent goals of consumer food packaging are to convey a food product from processor to consumer in a manner that seeks to limit damage from shipping and handling preserves freshness and helps to sell the product. While environment friendly may be an important ethical consideration for individual companies, no company is willing to sacrifice any of the above four in exchange for a truly reusable or recyclable package.

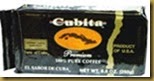

One only has to look at some of the more recent developments in packaging to see how these advancements can very easily be classified under one or more of the four reasons stated above. The almost global adoption of the one-way valve in the specialty coffee industry has increased the freshness of coffee for the consumer and reduced shipping damage, as fewer bags burst at the seams. The adoption of 12 ounces as the standard packaging size for the specialty industry has made coffee buying more convenient, as it more closely reflects consumption patterns of the average specialty coffee consumer, and increases freshness as well, as consumers buy in smaller quantities, more frequently. Better printing technology coupled with a move toward more professional, higher quality packaging graphics is all about shelf appeal and selling.

How?

Every coffee business is unique. Size of operation, customer demographic, distance from roasting facility to retailer, sales weight and ground or whole bean and location all can help dictate the type of packaging that is best suited for your product. For our industry the standard packaging material is currently a poly-foil bag with a one-way valve bearing either preprinted graphics or utilizing labels.

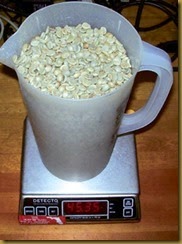

Many roasters begin their packaging operations with just a scale, a scoop and an impulse sealer, preformed stock poly-foil bags and labels. But even at this relatively unsophisticated level, it is important that roasters carefully consider their packaging options. It is a common misconception among roasters that there is very little that can be done packaging-wise between fully manual (scale and scoop) and fully automated vertical form, fill and seal (VFFS) equipment. Many roasters believe they either have to throw an exorbitant amount of labor at their packaging problems or spend a small fortune on a VFFS. However, this isn't the case. There a number of options between the two extremes that allow roasters to create packaging options that grow as they do.

While VFFS might seem like the best choice for those companies who plan to continue growing their business, there are additional factors to take into consideration. VFFS is great machinery that can add value to any roasting operation, but it is expensive and requires a much higher level of experience and/or technical know how to operate. Additionally, the majority of roasters in the specialty industry have very little need of packing 40- to 100-plus packages of coffee per minute. Those companies that do are generally more mature roasters with a good handle on all aspects of their businesses, or are operating in the food service and hospitality sectors of the coffee industry where large numbers of fractional packed coffee is required. To do VFFS equipment and other fully automated bagging equipment would require a separate investigation from the one described below.

So let's begin, where most of us begin, as small micro-roasters with a growing business, we can then "punch the numbers" to determine what is best suited for our operation.

Our motto for this exercise, as it should be in our businesses, is "profit maximization through labor efficiency" or "use the least amount of capital to replace the most amount of labor." It matters little if the labor is our own or our employees.

A Roadmap To Profitability

Pack coffee by hand for very long and you will soon notice that the evolution that takes the longest is getting the product in the bag at the correct weight. You will also notice that it can take you as long to weigh out and fill a four-ounce bag as a one-pound bag. Additionally, every so often you knock over or drop a bag moving from the scale to the sealer, increasing loss and the overall time it takes to package the order. This again increases your labor costs and reduces your profitability.

Pack coffee by hand for very long and you will soon notice that the evolution that takes the longest is getting the product in the bag at the correct weight. You will also notice that it can take you as long to weigh out and fill a four-ounce bag as a one-pound bag. Additionally, every so often you knock over or drop a bag moving from the scale to the sealer, increasing loss and the overall time it takes to package the order. This again increases your labor costs and reduces your profitability.

As the owner or manager of the business it is your direct responsibility to know what your options in packaging equipment are. You should ask yourself: How much will it cost to buy? How much will it cost to operate? And you should be able to discern the differences between often very similar pieces of equipment. Long-term sustainability of your business requires nothing less.

Before looking at equipment here are a few simple questions you should ask yourself. 1) What type of package is currently your biggest headache: weight, whole bean or ground? 2) What other types of packaging would you also like to stop doing by hand: weight, whole bean or ground? 3) Who is going to operate any new equipment: dedicated packaging person, roaster or other multi-tasking personnel? 4) How much money am I willing to spend to fix this problem? 5) What do I need the pay-back to be on the equipment for it to make economic sense to my business?

The first question is an identifying question: it helps you identify what you really need a piece of equipment to do, and do well. The second question is a wish question, as in "I wish this equipment also did this." The wish question may help to determine which piece of equipment you are going to purchase, or help determine if you are willing to spend a little more money for a little more flexibility. The third question is the "who" question; a dedicated operator can handle a more sophisticated piece of equipment or manage a more complex process than any multi-taskers. Additionally, there can be an added safety factor when requiring roasters to multi-task during roaster operations, highlighting the need for a less complex system. The money question is one on which to be both honest and careful. Next is the replacing labor question--how long before the labor efficiencies I realize from this purchase will completely pay back the capital I spent buying the equipment? Now with those questioned answered, let's move on to punching the numbers. Here are some ways to speed up the packaging process while ensuring an accurate end-result.

Step 1: Buy a Foot Sealer

A foot sealer reduces the number of hand movements it takes to move from the scale to a finished package. It also reduces loss since both hands remain on the package, reducing the number of spilled and or dropped bags. You are also left with a cleaner and more consistent seal.

However, not all foot sealers are the same. There are two types of foot sealers, manual (you supply the sealing pressure) and assist (you supply the signal, a motor or pneumatic ram supplies the pressure). Manual foot sealers are cheaper, but the seal can be less consistent than on the assist type and can be more fatiguing. Some assist sealers have the ability to seal multiple bags simultaneously.

Better foot sealers of both types may have the ability to imprint a changeable alphanumeric code into the seal. This function can be very important if grocery is in your future, as many grocery chains require a tamper proof recall plan.

Step 1: Foot Sealer

- Estimated Capital Expenditure

- $250-$1,250

Step 2: Buy an Automatic Filler

As noted above, the most labor intensive evolution in hand packaging is getting the weight into the bag. So our next purchase will be a machine that helps do just that: an automatic filler.

Automatic fillers come in three varieties; weigh and fills (automatic scales), auger fillers and volumetric or cup fillers. All have three components in common: a supply, or filling, hopper, some type of weighing mechanism and a foot pedal for manual use.

Of the three types, weigh and fills have the most flexibility without making a change in the configuration of the equipment. Weigh and fills utilize vibration to move the coffee, whole bean or ground, from the supply hopper to the weigh head, or scale. Most use two vibration settings. By changing the speed of the vibrations and duration of each it is fairly easy to change weights as well as type of coffees. Most weigh and fills can measure in a range of between two ounces and five pounds with a consistency of .1 ounce. It can sometimes be tricky to keep consistent, correct weight with very small fractional weights. Weigh and fills work well for both whole bean and ground, and are the best option for whole bean.

Auger fillers are by far the most popular fillers for use with high-speed packaging machines, especially when filling ground coffee. They are fast, clean and highly accurate, making them exceptionally good for fractional weights of ground coffee, but can also be used for whole bean coffee and heavier weights. Auger fillers "weigh" the coffee by counting the number of rotations it takes to get to the desired weight, the number of rotations is set by the operator and is easily changeable when changing coffees or weights. Large changes, especially from ground to whole bean, or from small weights to large weights may require a change in augers (tooling), making auger fillers less flexible than weigh and fills. Auger fillers can work well for both ground and whole bean, depending upon configuration, and are the best option if packing only ground coffee.

Volumetric cup fillers are the least used of the automatic fillers and are probably the least accurate as well. These fillers utilize a cup-in-cup system with one cup of a slightly larger diameter than the other, weights are adjusted by moving the smaller cup in or out of the larger thereby expanding the length of the entire cylinder. These cups are set in a rotating table that fills with coffee as the cups rotate under a feeder hopper and dispenses the coffee when the cups rotate over a void, filling the bag. While these fillers can be accurate, a change in cups or even rotating tables is often required when moving from small volume, light weights to large volume, heavier weights. Like auger fillers, the operator must check-weigh and set the cup volume for desired weights and consistency. Volumetric fillers can work for either whole bean or ground.

- Step 2: Automatic Filler

- Estimated Capital Expenditure

- $6000-$12,000

Speeding It Up

Okay so you have a foot sealer and an automatic scale--now, how fast can you really go? How many bags can you do in a week? A month? A year?

It is generally accepted that by using an automatic filler and a foot sealer, a novice can form (open and square the bag), fill and seal six bags per minute consistently. As opposed to a couple per minute with a scale, scoop and hand sealer.

Let us assume one dedicated packaging person at $10.00/hour labor.

6 bags/minute x 50 minutes

= 300 bags/hr

x 6 hrs

= 1800 bags/day

x 5 days

= 9000 bags/week

x 20 days

= 36,000 bags/month

x 12 months

= 432,000 bags/year

This gives you a per bag labor rate of between $.03-.05. So, with a capital investment of as little as $6,250 or as high as $13,250, you now have a packaging operation capable of easily producing nearly half a million bags of coffee a year at a conservative marginal labor rate of $.03-.05 per bag.

By adding something as simple as a bandsealer, you can nearly double that number to 10 bags/minute, making your numbers look something like this:

- Hourly 500 bags

- Daily 3,000 bags

- Weekly 15,000 bags

- Monthly 60,000 bags

- Yearly 720,000 bags

This will cause your per bag labor rate to fall to between $.02 and $.025.

What is a bandsealer? A bandsealer is a sealer with continuously moving bands that move a bag across a heated surface. A bandsealer is a "hands free" and "foot free" sealing device that enables the packager to quickly move to the next evolution--forming and filling the next bag. It incorporates all the advantages of a foot sealer but is quicker and less fatiguing to operate.

- Bandsealer

- Estimated Capital Expenditure

- $6,000-$9,000

So, with a total capital expenditure of between $12,000 and $21,000, a coffee roaster could very easily package over 700,000 bags/year. What's more, these decidedly low-tech pieces of equipment are easy to learn to use, last decades and retain a very high percentage of their initial value if resold. In other words, they are long term, scalable, flexible and labor efficient.

Looked at another way, one operator running an automatic filler and a foot sealer can handle nearly all the production of a 120-kilo roaster running one shift, if packed in 12-ounce bags. An automatic filler and a bandsealer could very nearly handle all the production of a 120 kilo roaster running two shifts.

But It Is Never As Easy As It Looks

While the numbers above are sound, if not a little too conservative, they are somewhat incomplete, even on the labor side. If a company is using preprinted bags (minimums between 10,000 and 20,000 units depending upon bag manufacturer) the labor numbers are sound. If however, a company buys stock bags and applies the labels themselves, then the labor numbers are surely incomplete. Applying labels to bags is what an economist would call a leakage. It is labor that generally goes unaccounted for in most roasters' cost of production. Manually applying front and back labels only compounds the flow of the leak. And applying labels can be labor intensive.

There are three possible solutions to the problem. Account and adjust price accordingly (even if using "dead labor," such as retail labor during slow hours, the costs of this labor should still be accounted for in the price) to maintain desired margins. Buy a label peeler that peels the back of the label making it easier (read: less labor) to apply labels. Or pay the bag manufacturer to "blow" the labels on. One bag manufacturer charges $.06 to apply a label to a bag. So time yourself and do the math. One advantage to having the label blown on is that it is nearly always straight and centered, which is sometimes tough to do by hand.

Tin ties, resealable tape and zip locks are also areas where significant labor leakages can occur. This is especially true of tin ties that are folded on the bag to look like a seal, instead of just stuck to the side for later use by the consumer. Since this type of tin tie is the most labor intensive and, unfortunately, must be done in-house after the bag is sealed, this labor must be accounted for in the cost of production. A good number for folding down the bag and applying a tin tie would be five/minute (or $.033/bag in additional labor costs). This is longer and therefore more expensive, than forming, filling and sealing the bag.

Other areas where significant labor leakages may occur include conveying and loading; the impact of both of which can be lessened with better production layout, using other non-assigned labor, such as the roaster operator, or by adding more equipment (loaders and conveyors) or a combination of any of these. And also boxing and preparing for shipping.

At the end of the day, it is our goal as roasters and businesses owners to find that perfect balance between capital input and labor. It is a deceivingly simple mathematics problem that must be constantly refigured as our businesses continue to grow and change. Find the right balance and you will be profitable, run for a long while out of balance and you may very well find yourself working harder and making less.

Material Costs

OF COURSE, labor is only one of the costs associated with packaging. Listed below are some good ballpark bag and label costs.

- One-pound valve bags $.25

- Pre-printed labels $.08

- Labels applied $.06

- Pre-printed bags $.22

- Tin Ties $.03

- Resealable tape $.005

Remember to ask good questions of your material supplier, who is often one of the most experienced packaging people in the business.

- What is the minimum order?

- Are there additional charges, such as for art or plates?

- What is the lead time?

- Are there other material/bag options for my packaging operation?

Leader of Packaging

IN THE LATE SUMMER of 2005, a small group of coffee roasters visited a fourth-generation coffee roasting company located in St. Louis, Mo.--Chauvin Coffee Company. As president, the late Dave Charleville, gave a tour of his facility and answered questions regarding his operation. As all of the roasters on the visit were running operations much smaller than Charleville's, many had questions about Chauvin's packaging equipment. When asked how to choose the proper packaging equipment and when to purchase it, Charleville gave an answer that was both insightful and incredibly helpful. "Always buy capital equipment for the long term," he said. "Make absolutely sure that it makes your operation more labor efficient, and make sure that it is flexible and scalable."

If one were to survey professional roasters, and the owners of wholesale roasting facilities to find out what area of the production process consistently gives them the most headaches, there can be little doubt that the overwhelming answer would be packaging. Furthermore, it is in the packaging of coffee, from opening and forming the bags and filling them accurately to labeling and applying resealables--be they tin ties, resealable tape or zip locks--where coffee roasters lose the most control over their labor costs. If roasters look closely, many will find their shrinking or non-existent profits are a result of inaccurately accounting for packaging labor.

Choose the wrong material or use poorly considered art and sales will suffer; choose the wrong piece or combination of pieces of packaging equipment and labor costs will rise. And while it is relatively easy to figure the costs of material in a package (bag + label(s) + tin tie), it is much more difficult to figure labor costs per package.

So if packaging coffee is so problematic, why undertake it at all?

Why?

There are four reasons for consumer food packaging, all of which are relevant to coffee: 1) To convey the product from processor to consumer in a convenient manner 2) To preserve product freshness 3) To protect the product from shipping damage 4) To sell the product

To put this in one statement, it would go something like this: The interdependent goals of consumer food packaging are to convey a food product from processor to consumer in a manner that seeks to limit damage from shipping and handling preserves freshness and helps to sell the product. While environment friendly may be an important ethical consideration for individual companies, no company is willing to sacrifice any of the above four in exchange for a truly reusable or recyclable package.

One only has to look at some of the more recent developments in packaging to see how these advancements can very easily be classified under one or more of the four reasons stated above. The almost global adoption of the one-way valve in the specialty coffee industry has increased the freshness of coffee for the consumer and reduced shipping damage, as fewer bags burst at the seams. The adoption of 12 ounces as the standard packaging size for the specialty industry has made coffee buying more convenient, as it more closely reflects consumption patterns of the average specialty coffee consumer, and increases freshness as well, as consumers buy in smaller quantities, more frequently. Better printing technology coupled with a move toward more professional, higher quality packaging graphics is all about shelf appeal and selling.

How?

Every coffee business is unique. Size of operation, customer demographic, distance from roasting facility to retailer, sales weight and ground or whole bean and location all can help dictate the type of packaging that is best suited for your product. For our industry the standard packaging material is currently a poly-foil bag with a one-way valve bearing either preprinted graphics or utilizing labels.

Many roasters begin their packaging operations with just a scale, a scoop and an impulse sealer, preformed stock poly-foil bags and labels. But even at this relatively unsophisticated level, it is important that roasters carefully consider their packaging options. It is a common misconception among roasters that there is very little that can be done packaging-wise between fully manual (scale and scoop) and fully automated vertical form, fill and seal (VFFS) equipment. Many roasters believe they either have to throw an exorbitant amount of labor at their packaging problems or spend a small fortune on a VFFS. However, this isn't the case. There a number of options between the two extremes that allow roasters to create packaging options that grow as they do.

While VFFS might seem like the best choice for those companies who plan to continue growing their business, there are additional factors to take into consideration. VFFS is great machinery that can add value to any roasting operation, but it is expensive and requires a much higher level of experience and/or technical know how to operate. Additionally, the majority of roasters in the specialty industry have very little need of packing 40- to 100-plus packages of coffee per minute. Those companies that do are generally more mature roasters with a good handle on all aspects of their businesses, or are operating in the food service and hospitality sectors of the coffee industry where large numbers of fractional packed coffee is required. To do VFFS equipment and other fully automated bagging equipment would require a separate investigation from the one described below.

So let's begin, where most of us begin, as small micro-roasters with a growing business, we can then "punch the numbers" to determine what is best suited for our operation.

Our motto for this exercise, as it should be in our businesses, is "profit maximization through labor efficiency" or "use the least amount of capital to replace the most amount of labor." It matters little if the labor is our own or our employees.

A Roadmap To Profitability

Pack coffee by hand for very long and you will soon notice that the evolution that takes the longest is getting the product in the bag at the correct weight. You will also notice that it can take you as long to weigh out and fill a four-ounce bag as a one-pound bag. Additionally, every so often you knock over or drop a bag moving from the scale to the sealer, increasing loss and the overall time it takes to package the order. This again increases your labor costs and reduces your profitability.

As the owner or manager of the business it is your direct responsibility to know what your options in packaging equipment are. You should ask yourself: How much will it cost to buy? How much will it cost to operate? And you should be able to discern the differences between often very similar pieces of equipment. Long-term sustainability of your business requires nothing less.

Before looking at equipment here are a few simple questions you should ask yourself. 1) What type of package is currently your biggest headache: weight, whole bean or ground? 2) What other types of packaging would you also like to stop doing by hand: weight, whole bean or ground? 3) Who is going to operate any new equipment: dedicated packaging person, roaster or other multi-tasking personnel? 4) How much money am I willing to spend to fix this problem? 5) What do I need the pay-back to be on the equipment for it to make economic sense to my business?

The first question is an identifying question: it helps you identify what you really need a piece of equipment to do, and do well. The second question is a wish question, as in "I wish this equipment also did this." The wish question may help to determine which piece of equipment you are going to purchase, or help determine if you are willing to spend a little more money for a little more flexibility. The third question is the "who" question; a dedicated operator can handle a more sophisticated piece of equipment or manage a more complex process than any multi-taskers. Additionally, there can be an added safety factor when requiring roasters to multi-task during roaster operations, highlighting the need for a less complex system. The money question is one on which to be both honest and careful. Next is the replacing labor question--how long before the labor efficiencies I realize from this purchase will completely pay back the capital I spent buying the equipment? Now with those questioned answered, let's move on to punching the numbers. Here are some ways to speed up the packaging process while ensuring an accurate end-result.

Step 1: Buy a Foot Sealer

A foot sealer reduces the number of hand movements it takes to move from the scale to a finished package. It also reduces loss since both hands remain on the package, reducing the number of spilled and or dropped bags. You are also left with a cleaner and more consistent seal.

However, not all foot sealers are the same. There are two types of foot sealers, manual (you supply the sealing pressure) and assist (you supply the signal, a motor or pneumatic ram supplies the pressure). Manual foot sealers are cheaper, but the seal can be less consistent than on the assist type and can be more fatiguing. Some assist sealers have the ability to seal multiple bags simultaneously.

Better foot sealers of both types may have the ability to imprint a changeable alphanumeric code into the seal. This function can be very important if grocery is in your future, as many grocery chains require a tamper proof recall plan.

Step 1: Foot Sealer

- Estimated Capital Expenditure

- $250-$1,250

Step 2: Buy an Automatic Filler

As noted above, the most labor intensive evolution in hand packaging is getting the weight into the bag. So our next purchase will be a machine that helps do just that: an automatic filler.

Automatic fillers come in three varieties; weigh and fills (automatic scales), auger fillers and volumetric or cup fillers. All have three components in common: a supply, or filling, hopper, some type of weighing mechanism and a foot pedal for manual use.

Of the three types, weigh and fills have the most flexibility without making a change in the configuration of the equipment. Weigh and fills utilize vibration to move the coffee, whole bean or ground, from the supply hopper to the weigh head, or scale. Most use two vibration settings. By changing the speed of the vibrations and duration of each it is fairly easy to change weights as well as type of coffees. Most weigh and fills can measure in a range of between two ounces and five pounds with a consistency of .1 ounce. It can sometimes be tricky to keep consistent, correct weight with very small fractional weights. Weigh and fills work well for both whole bean and ground, and are the best option for whole bean.

Auger fillers are by far the most popular fillers for use with high-speed packaging machines, especially when filling ground coffee. They are fast, clean and highly accurate, making them exceptionally good for fractional weights of ground coffee, but can also be used for whole bean coffee and heavier weights. Auger fillers "weigh" the coffee by counting the number of rotations it takes to get to the desired weight, the number of rotations is set by the operator and is easily changeable when changing coffees or weights. Large changes, especially from ground to whole bean, or from small weights to large weights may require a change in augers (tooling), making auger fillers less flexible than weigh and fills. Auger fillers can work well for both ground and whole bean, depending upon configuration, and are the best option if packing only ground coffee.

Volumetric cup fillers are the least used of the automatic fillers and are probably the least accurate as well. These fillers utilize a cup-in-cup system with one cup of a slightly larger diameter than the other, weights are adjusted by moving the smaller cup in or out of the larger thereby expanding the length of the entire cylinder. These cups are set in a rotating table that fills with coffee as the cups rotate under a feeder hopper and dispenses the coffee when the cups rotate over a void, filling the bag. While these fillers can be accurate, a change in cups or even rotating tables is often required when moving from small volume, light weights to large volume, heavier weights. Like auger fillers, the operator must check-weigh and set the cup volume for desired weights and consistency. Volumetric fillers can work for either whole bean or ground.

- Step 2: Automatic Filler

- Estimated Capital Expenditure

- $6000-$12,000

Speeding It Up

Okay so you have a foot sealer and an automatic scale--now, how fast can you really go? How many bags can you do in a week? A month? A year?

It is generally accepted that by using an automatic filler and a foot sealer, a novice can form (open and square the bag), fill and seal six bags per minute consistently. As opposed to a couple per minute with a scale, scoop and hand sealer.

Let us assume one dedicated packaging person at $10.00/hour labor.

6 bags/minute x 50 minutes

= 300 bags/hr

x 6 hrs

= 1800 bags/day

x 5 days

= 9000 bags/week

x 20 days

= 36,000 bags/month

x 12 months

= 432,000 bags/year

This gives you a per bag labor rate of between $.03-.05. So, with a capital investment of as little as $6,250 or as high as $13,250, you now have a packaging operation capable of easily producing nearly half a million bags of coffee a year at a conservative marginal labor rate of $.03-.05 per bag.

By adding something as simple as a bandsealer, you can nearly double that number to 10 bags/minute, making your numbers look something like this:

- Hourly 500 bags

- Daily 3,000 bags

- Weekly 15,000 bags

- Monthly 60,000 bags

- Yearly 720,000 bags

This will cause your per bag labor rate to fall to between $.02 and $.025.

What is a bandsealer? A bandsealer is a sealer with continuously moving bands that move a bag across a heated surface. A bandsealer is a "hands free" and "foot free" sealing device that enables the packager to quickly move to the next evolution--forming and filling the next bag. It incorporates all the advantages of a foot sealer but is quicker and less fatiguing to operate.

- Bandsealer

- Estimated Capital Expenditure

- $6,000-$9,000

So, with a total capital expenditure of between $12,000 and $21,000, a coffee roaster could very easily package over 700,000 bags/year. What's more, these decidedly low-tech pieces of equipment are easy to learn to use, last decades and retain a very high percentage of their initial value if resold. In other words, they are long term, scalable, flexible and labor efficient.

Looked at another way, one operator running an automatic filler and a foot sealer can handle nearly all the production of a 120-kilo roaster running one shift, if packed in 12-ounce bags. An automatic filler and a bandsealer could very nearly handle all the production of a 120 kilo roaster running two shifts.

But It Is Never As Easy As It Looks

While the numbers above are sound, if not a little too conservative, they are somewhat incomplete, even on the labor side. If a company is using preprinted bags (minimums between 10,000 and 20,000 units depending upon bag manufacturer) the labor numbers are sound. If however, a company buys stock bags and applies the labels themselves, then the labor numbers are surely incomplete. Applying labels to bags is what an economist would call a leakage. It is labor that generally goes unaccounted for in most roasters' cost of production. Manually applying front and back labels only compounds the flow of the leak. And applying labels can be labor intensive.

While the numbers above are sound, if not a little too conservative, they are somewhat incomplete, even on the labor side. If a company is using preprinted bags (minimums between 10,000 and 20,000 units depending upon bag manufacturer) the labor numbers are sound. If however, a company buys stock bags and applies the labels themselves, then the labor numbers are surely incomplete. Applying labels to bags is what an economist would call a leakage. It is labor that generally goes unaccounted for in most roasters' cost of production. Manually applying front and back labels only compounds the flow of the leak. And applying labels can be labor intensive.

There are three possible solutions to the problem. Account and adjust price accordingly (even if using "dead labor," such as retail labor during slow hours, the costs of this labor should still be accounted for in the price) to maintain desired margins. Buy a label peeler that peels the back of the label making it easier (read: less labor) to apply labels. Or pay the bag manufacturer to "blow" the labels on. One bag manufacturer charges $.06 to apply a label to a bag. So time yourself and do the math. One advantage to having the label blown on is that it is nearly always straight and centered, which is sometimes tough to do by hand.

Tin ties, resealable tape and zip locks are also areas where significant labor leakages can occur. This is especially true of tin ties that are folded on the bag to look like a seal, instead of just stuck to the side for later use by the consumer. Since this type of tin tie is the most labor intensive and, unfortunately, must be done in-house after the bag is sealed, this labor must be accounted for in the cost of production. A good number for folding down the bag and applying a tin tie would be five/minute (or $.033/bag in additional labor costs). This is longer and therefore more expensive, than forming, filling and sealing the bag.

Other areas where significant labor leakages may occur include conveying and loading; the impact of both of which can be lessened with better production layout, using other non-assigned labor, such as the roaster operator, or by adding more equipment (loaders and conveyors) or a combination of any of these. And also boxing and preparing for shipping.

At the end of the day, it is our goal as roasters and businesses owners to find that perfect balance between capital input and labor. It is a deceivingly simple mathematics problem that must be constantly refigured as our businesses continue to grow and change. Find the right balance and you will be profitable, run for a long while out of balance and you may very well find yourself working harder and making less.

Material Costs

OF COURSE, labor is only one of the costs associated with packaging. Listed below are some good ballpark bag and label costs.

- One-pound valve bags $.25

- Pre-printed labels $.08

- Labels applied $.06

- Pre-printed bags $.22

- Tin Ties $.03

- Resealable tape $.005

Remember to ask good questions of your material supplier, who is often one of the most experienced packaging people in the business.

- What is the minimum order?

- Are there additional charges, such as for art or plates?

- What is the lead time?

- Are there other material/bag options for my packaging operation?